INTERVIEW: Olivia Ahmad on curating a major exhibition of Soviet children’s picture books at the House of Illustration

Olivia Ahmad is the curator at the House of Illustration, established in London in 2002. She is responsible for its exhibitions programme and artistic residencies, and recently curated A New Childhood: Picture books from Soviet Russia. We have met with Olivia to talk about the ideas behind this show, important works and artists of the period and how the UK publishing was influenced by the Soviet picture books.

Anna Prosvetova: Olivia, could you tell us more about the story behind this exhibition?

Olivia Ahmad: I discovered this period in Russian children’s literature through a book called Inside the Rainbow, published by Redstone Press in 2013. It was such a revelation-the illustrations really captured my imagination. When I joined House of Illustration in 2014, our director Colin McKenzie and I talked about the book. He also really loved the material, and it became our ambition to create an exhibition about early Soviet picture books. House of Illustration does a series of changing exhibitions about illustration in all its forms – picture books of the 1920s and early 1930s are so important in the history of Russian graphic arts, but also in the history of picture books more broadly, so it seemed essential for us to do an exhibition about it. We contacted Julian Rothenstein, the publisher of Inside the Rainbow, who kindly introduced us to Sasha Lurye, whose collection was the basis of the book. Sasha generously allowed us to select the works from his collection for the show.

AP: Could you tell more about this collection?

OA: Sasha Lurye has been collecting Soviet picture books for more than twenty years and I believe he has amassed the biggest collection of this material in the world. It includes books and posters, but also original illustrations and sketches, which you can see in this exhibition. For example, we have original designs by Natan Altman and Vera Ermolaeva, and preparatory sketches by Vladimir Lebedev – incredibly rare material. Sasha Lurye’s collection is very broad, and the works on display (around 120 pieces) are only a tip of an iceberg.

Installation view / Photo by Anna Prosvetova

AP: Have you worked with academic consultants or Russian museums during the preparation of the show?

OA: I worked with Frances Saddington from the University of East Anglia. Frances is undertaking postgraduate research in early Soviet book illustration. Many elements need to be appreciated when looking at this material – the changing social, political and economic context, but also debates about what Soviet picture books should look like and the development of avant-garde art movements. It is also essential to understand the text, and in particular to be able to hear poetry read aloud so that the rhythm and the melody of the text can be appreciated. Frances worked with me to select artworks and to interpret them with all these elements under consideration.

“The propagandist element of early Soviet picture books is very interesting, but it is just a small part of a bigger story, and we wanted to make this clear in our show.”

AP: How did you structure the material in the exhibition?

OA: As well as showing stunning illustration, there were two things we wanted to say in this exhibition. First of all, that this amazing period of the 1920s did not develop in isolation, so we wanted to reference the pre-revolutionary books, that influenced the early Soviet period. Also, we wanted to present the diversity of the 1920s in terms of aesthetics and subject matter.

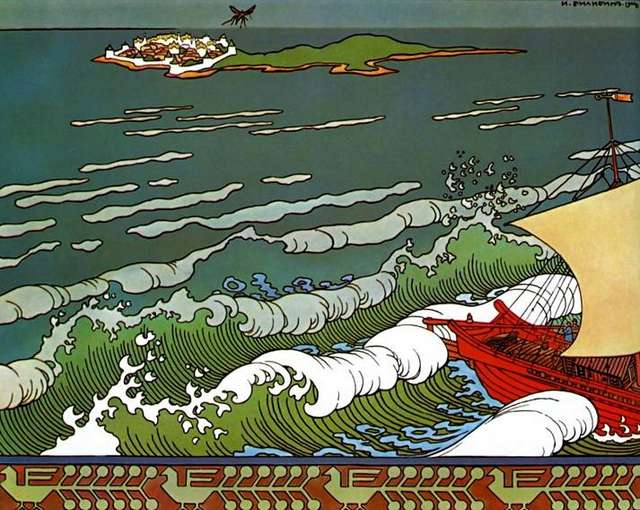

The first section of the show is about the pre-revolutionary books, which are different from the later period in character, but very important in the development of picture books. For instance, in this book of fairy tales by Ivan Bilibin you can see that the pages are carefully designed, the font and positioning of the text is considered as a part of the whole structure. The viewpoints of the illustrations are very dramatic, taking their inspiration from other aesthetic traditions of the time, such as Japanese prints. Here is an interesting pre-revolutionary book from 1911, The Firebird, a collection of stories with a poem by Kornei Chukovsky, illustrated by Sergei Chekhonin. You can see here that while keeping the traditional format of a hardback book, there are innovations in the page design: loud sounds, such as a cockerel crowing are in large letters, and the illustrations are interspersed through the text rather than separated. We might take things like this for granted in picture books now, but at the time this was an inventive thing to do.

Ivan Bilibin, illustration to ‘The Tale of Tsar Saltan’, 1905 / Courtesy of Wikiart.org

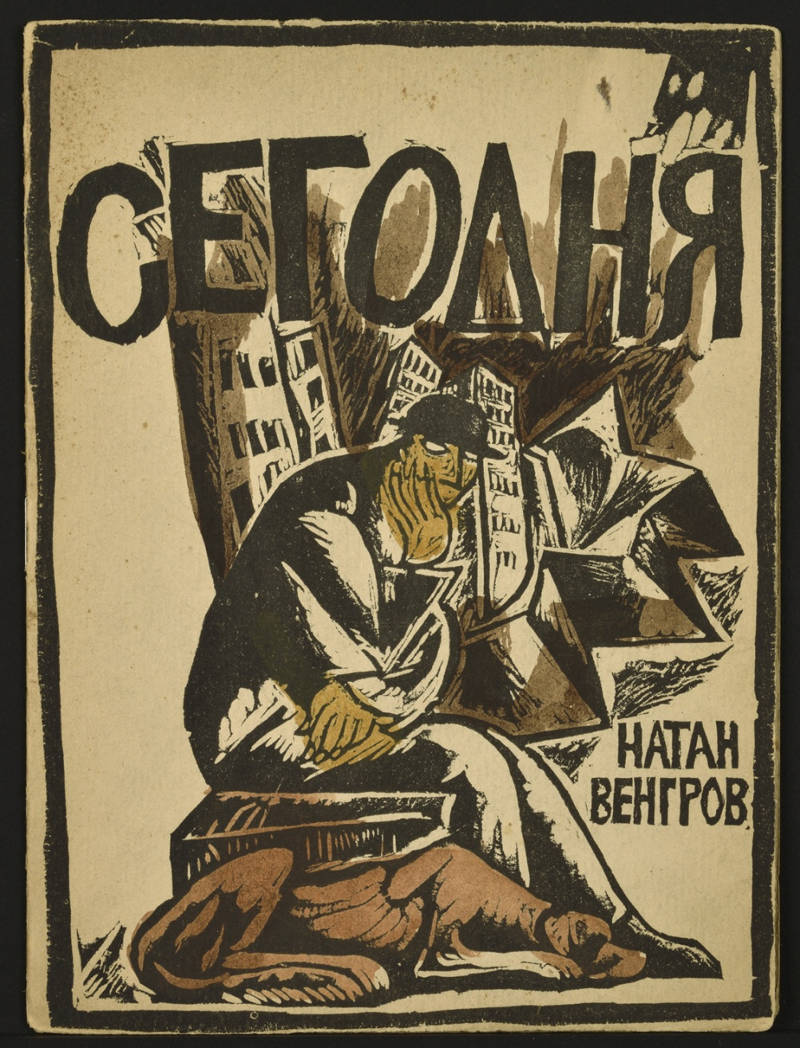

We also have a selection of works by Segodnya collective, who were the first Soviet children’s book publisher. Segodnya was a small collective of avant-garde artists and writers, organised by Vera Ermolaeva. At the time publishing books in Soviet Russia was really difficult because of material shortages as a result of the First World War and the Civil War, but this group got around this by hand-printing books and lubok prints. You can see that they are interested in the traditional formats of the seventeenth century, but they were also interested in Modernism. Segodnya’s publications are so important, because they make a link between Russian Futurist books and picture book illustration by the Russian Avant-garde later on.

Today by Vera Ermolaeva, 1919 / Courtesy of the House of Illustration

We also feature Yiddish picture books in the introduction to the exhibition. Before the Revolution there was a tsarist ban on Yiddish publishing – after the Revolution it was lifted. That allowed modern artists we know really well, such as Marc Chagall and El Lissitzky, to express their interest in Modernism and their Jewish heritage for the first time. In El Lissitzky’s Had Gadya, the traditional song sung during Passover is illustrated with fragmented shapes.

AP: I understand that the display dedicated to the books after the Revolution is divided by themes.

OA: That’s right, this is because we wanted it to be clear that it was a very diverse period in terms of subject matter and aesthetics – while there were fascinating books about politics and industrial development, there were also contemporary fairy tales, illustrated translations of Western literature and books about toys and the circus.

AP: What period are you looking at in this exhibition?

OA: The main part of the exhibition starts in 1921, the introduction of the New Economic Policy, and it runs until the early 1930s, after which Socialist Realism became the officially adopted aesthetic approach.

We wanted to focus our show on this early period because it was such a free period of experimentation; avant-garde artists and celebrated pre-revolutionary illustrators were working alongside each other and creating a huge number of picture books.

In the immediate years after the Revolution, publishing slowed almost to a stop, but in 1921 the introduction of the New Economic Policy really jump-started the industry and there were many private publishing houses as well as the state publisher. Almost 10,000 books were published during this period, and in large editions, sometimes more than 200,000. Picture books were really a mass-media phenomenon.

“In the immediate years after the Revolution, publishing slowed almost to a stop, but in 1921 the introduction of the New Economic Policy really jump-started the industry…”

We introduce the 1920s with a poster by Olga and Galina Chichagova – one side it says “Out with the mysticism and fantasy of children’s books!” with pictures of Baba Yaga, the witch of Slavic folklore, the Firebird and Kornei Chukovsky’s Crocodile. On the other side of the poster we have a constructivist vision of the future, with images of Lenin, young Pioneers, factories and farming with the caption “Give us a new children’s book, the new reality of childhood!”. This poster reflects debates that were on going during the 1920s-politicians and theorists were concerned that fantasy may be an unhelpful distraction for children and that books should have socialist priorities at their core. In practice however, these debates were largely theoretical in the early Soviet period, and there were books on many subjects, including contemporary fairy tales.

Poster by Olga and Galina Chichagova / Courtesy of the House of Illustration

AP: Art of the Russian Avant-Garde is well-known in the West, and it is frequently associated with the propaganda of the Soviet regime. Could you say that the children’s books were also illustrated only with the idea to spread the propagandist message to a younger generation?

OA: There were books that could be viewed as propagandist – books reflecting the excitement about the new government and the socialist future ahead, or books that described the key events and political figures of the Revolution. However, many books were based on everyday themes. Mechanised transport for example, was an emblem of Soviet progress, but at the same time ‘travel’ can be seen as a classic theme in children’s literature, regardless of political context. There were also many contemporary skazka, such as works by Kornei Chukovsky, which had no apparent connection to socialism. I think the propagandist element of early Soviet picture books is very interesting, but it is just a small part of a bigger story, and we wanted to make this clear in our show.

AP: It is interesting to see how during this period and also during the 1960-70s avant-garde and nonconformist artists such as Eric Bulatov and Ilya Kabakov worked as children’s books illustrators. Do you think this publishing activity was less governed by the state, allowing the artists to freely express their creative ideas?

OA: There was a lot of debate related to children’s books at that time. For example, Nadezhda Krupskaya, Lenin’s wife, described Chukovsky’s Crocodile as “bourgeois dregs”. There was some tension and opposition to books that were seen as deviating from Soviet priorities in the 1920s and early 30s, but I do not think that it really affected illustrators until later. There was a state sensor, but in practice books were rarely banned at this point.

AP: Do you know if this period in Soviet publishing and design influenced Western artists during this period or later?

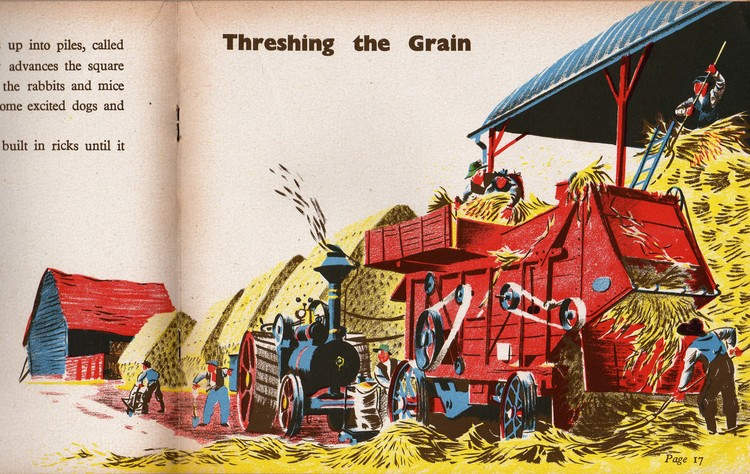

OA: It certainly did-Soviet books were exported to Western Europe and émigré Russian graphic artists were highly influential – such as Nathalie Perrain (née Tchelpanova) who worked in Paris on the Pere Castor albums and other titles. In the UK, the iconic Puffin Picture Books that were published from 1940 were directly influenced by early Soviet picture books. British artist Pearl Binder collected picture books on a visit to Russia in the 1930s, and showed them to publisher Noel Carrington. He was inspired by the power of the illustrations, but also the idea that books with colour illustrations could be printed cheaply, and therefore be made available to lots of children. The illustrators of these books worked directly on lithographic plates to create images made up of several colours.

One of the Puffin Picture Books / Courtesy of designfortoday.co.uk

AP: Why do you think this exhibition may be interesting to a contemporary viewer in London?

OA: Anybody who is interested in design and illustration should come and see this show because the books represent one of the most innovative periods in book design and illustration – many of the images seem strikingly contemporary, even today.

The images themselves represent bold experimentation with abstraction and primitivism, but they are also interesting in terms of their form. There are leporello books, and a book of The 5 Year plan that folds out to more than 2 metres in length and has a series of folds that open out to show the planned expansion of industries such as agriculture and iron production. Another book, How the Pioneer Hans Saved the Strike Committee, is printed as a series of ‘film strips’ that can be cut out and projected.

The works also present a fascinating combination of creative and political ideas, and questions the social role of children’s literature.

AP: In this exhibition you have works by some famous avant-garde artists, including Deineka and El Lissitzky. Could you tell us about some illustrators, who are less known?

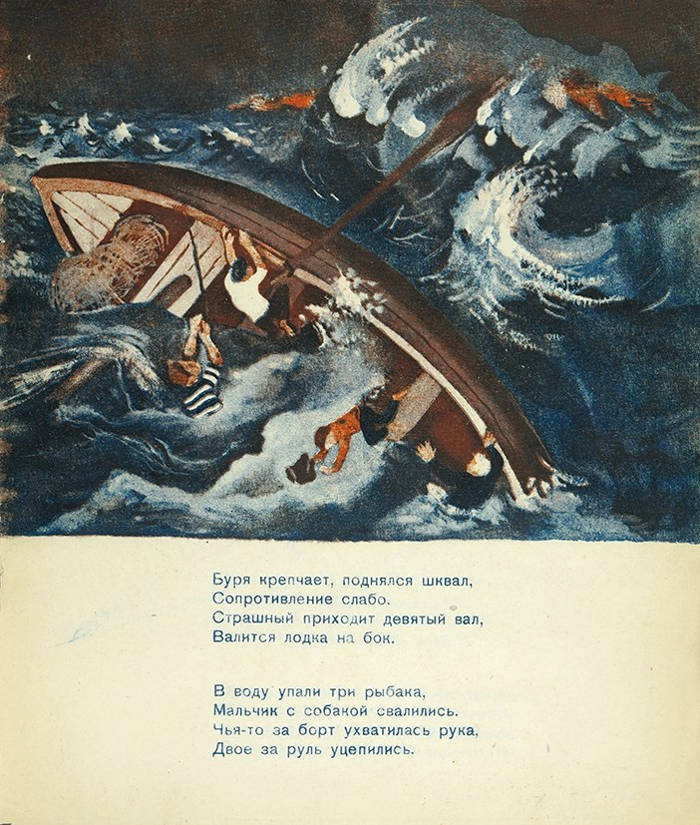

OA: The work of Vera Ermolaeva was a real revelation to me. We mentioned her earlier in relation to Segodnya group. She was not only a great artist, but she was also a great organiser and educator – she worked in Vitebsk with Kazimir Malevich and was a prominent figure in the avant-garde. In 1917/18 produced outstanding Futurist-inspired linocut children’s books. She later experimented with different materials and approaches to image-making. This is one of her books called The Fisherman. You can see that they way she worked is completely different to anybody else: it is a singular, almost painterly style. What I really love about her is that she was a great painter, but she also understood printing and created this tremendous depth and texture in her work through lithography.

Vera Ermolaeva, The Fisherman, 1930 / Courtesy of www.litfund.ru

We have a very fun book in the show illustrated by Ermolaeva, called Little Girls, which is about girls from different countries. They meet up to play and swap their clothes, but cannot remember whose are whose when it’s time to go home. In this book you have these mismatched heads, legs and bodies on each page. You cut along the page, following the lines, and then flip sections over until you match the right elements. We also display her original gouache drawings for the book, where you can see how she is designing the pages and making sure the format works.

AP: What are your personal highlights of the show?

OA: Vladimir Lebedev is one of the leading figures of this period, and his illustrations are very well-known today. His illustrations for books such as Circus and The Hunt build images using bold shapes made of flat colour – referencing his previous work making posters using stencils. In the exhibition, we are privileged to be showing Lebedev’s preparatory sketches for these two books. They are small, very tactile pencil drawings from which you can see how he is working out composition and determining the rhythm of the books. It’s very moving to see the humble beginnings of such iconic works.

Vladimir Lebedev, ‘The Hunt’ and the dummy book for ‘The Hunt’, 1925 / Courtesy of the House of Illustration

AP: Are there any events related to the exhibition?

OA: It is a huge subject, so much bigger than we could possible talk about in the exhibition, and so my colleague Michael Czerwinski is planning a series of talks about the influence of Soviet picture books on British publishing, and about the historic context. There also will be discussions with contemporary illustrators on how their work has been influenced by early Soviet aesthetics.

AP: Are you planning any future projects, related to this collection of Sasha Lurye? May be something dedicated to the centenary of the Russian Revolution?

OA: There are no fixed plans yet, but we would be delighted if there were opportunities to collaborate further in future. I personally find this period fascinating.

AP: Thank you, Olivia!

A New Childhood: Picture books from Soviet Russia at House of Illustration 27 May – 11 September 2016.

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.