INTERVIEW: Michael Boyd on staging Eugene Onegin for Garsington Opera

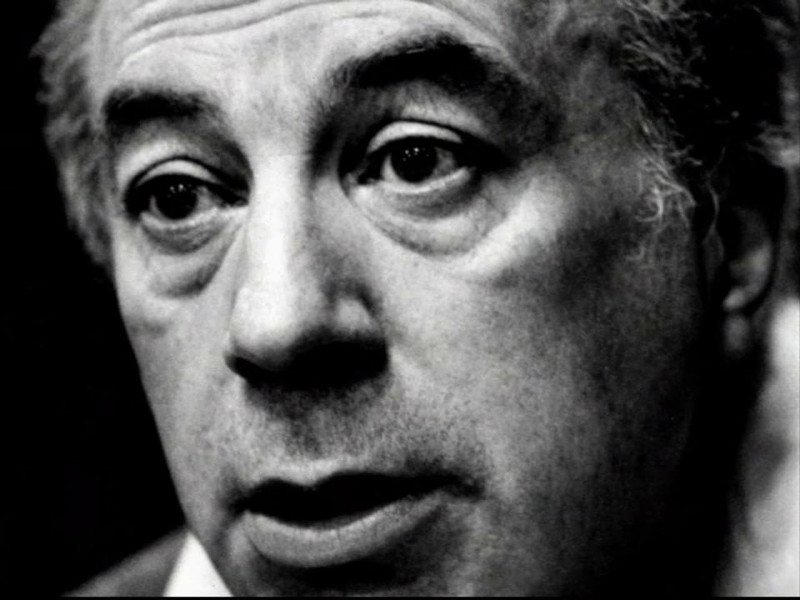

Above: Michael Boyd / Photo by Sarah Lee

Sir Michael Boyd was born in Belfast and studied English at Edinburgh University. In 1979 he won a British Council fellowship to study as trainee director under Anatoly Efros at the Malaya Bronnaya Theatre, Moscow. He joined the Royal Shakespeare Company as associate director in 1996 and was artistic director of the company 2002–12. Major events of his tenure at the RSC included the development of the new Royal Shakespeare Theatre (opened in 2011), the Complete Works Festival in 2006, the celebration of the company’s 50th anniversary in 2011 and the 2012 World Shakespeare Festival in association with the London Olympics.

He has also directed many new productions, including an Olivier Award-winning series of the History plays 2006–08. He was knighted in 2012. Director Michael Boyd made his operatic debut in 2015, directing Orfeo with the Royal Opera at the Roundhouse. We talked to Sir Boyd about his recent work on Eugene Onegin for Garsington Opera at Wormsley and the role of theatre today.

Roderick Williams (Onegin) and Natalya Romaniw (Tatyana) / credit Mark Douet

Anna Prosvetova: Michael, thank you for your time and congratulations on your Eugene Onegin opera at Garsington Opera. Could you tell us more about your experience of staging opera and how it is different from your previous work with Shakespeare and drama productions? What was your biggest challenge in this transition?

Michael Boyd: Onegin was my second opera production, as I did a production of Orfeo with Royal Opera at the Rooundhouse in 2015. As for the Garsington production, I suppose my biggest challenge was reconciling Pushkin’s Onegin with Tchaikovsky’s Onegin. In Pushkin’s work we are taken through Eugene Onegin by a very playful poet, a bit like Pushkin himself, and quite like Onegin. He tells the entire story with quite an ironic, humorous and socially-observant view. Tchaikovsky is so utterly for the emotional charge of a certain moment. Also, he introduces us to the opera entirely through the point of view of Tatiana.

I tried to look at Tchaikovsky’s opera through Pushkin’s eyes. It is known that for personal reasons Tchaikovsky had invested heavily in Tatiana, and I think it is wonderful. I decided to give the first half from Tatiana’s point of view, and then from the second half it will be almost solely Onegin, and then in the last scene we will have a punch-up between the two of them.

AP: What was your particular interest in this story and Tchaikovsky’s opera? Why do you think this story might be interesting for British audiences today?

MB: It all started with Pushkin, and Tchaikovsky came next. I think I would answer that question differently if it was about Pushkin’s Onegin, which I think is an attempt, in some ways, to paint a portrait of Russia. Tchaikovsky’s work is an attempt to paint a portrait of yearning, of missed opportunities in love, of the pressure on the individual. Tchaikovsky’s investment is on the emotional life of the individual, at the same time, unsurprisingly, providing a social commentary. It is relevant for a contemporary audience because of its direct emotional resonance around for example, – rejection in love, having a fork in the road of life – you take one turn and then you regret it later. It is about regret, remorse, conformism and non-conformism…

AP: I know that you have been working with the original Russian libretto. What was the main challenge in this process?

Roderick Williams (Onegin) / credit Mark Douet

MB: The decision to perform in Russian was not my decision, that was the Garsington Opera’s decision. If it had been up to me, I would probably have commissioned a contemporary poet to translate it. I think it is always more possible to make a direct connection with an audience in their own language, and I do not think it is beyond a capacity of a poet. It is a very difficult task, but I do not think it is impossible for a poet to make the transition lyrically from one language to another. When I worked on Orfeo, I commissioned the Scottish poet, Don Paterson, to translate the libretto from the Italian, and it was exquisite what he came up with. Of course, the Russian language has some properties that would be lost in translation, but on balance I am prejudiced in the favour of thinking about art as communication, and the more direct the better.

AP: There are many contemporary interpretations of classical works today, but in your production the costumes reflect the fashions of the nineteenth century, when the story is set. What was the inspiration behind the choice of costumes?

MB: I think the relationships between the characters are shaped by the views of the time. I find this also very often in Shakespeare, when you transpose Shakespeare from the sixteenth or seventeenth centuries, certain behaviours are hard to understand. While I am in favour of translation into a local language, translation of a period, which I have done many times, is even harder than the linguistic translation. Cultural translation through history is very difficult. We decided to go for an abstract, symbolist version of the 1820s to make it accurate. Nonetheless, visually it is pierced through by Abstraction, Modernism and Surrealism in a way that I hope stops it being a mere historical drama.

Roderick Williams (Onegin), Natalia Romaniw (Tatyana) / credit Mark Douet

AP: Garsington Opera is a place with a great history and wonderful setting. Could you tell us more about your overall experience of working there?

MB: The thing I really like about Garsington is the dedication and professionalism of everyone involved. Everybody is there for that short season, because they want to be there. It is a small, very compact company, with an intimate atmosphere, where everybody knows each other. There is a good communication between everybody, and it is a good creative environment.

AP: Why do you think there is such a strong interest in Russian opera today?

MB: There is a very strong repertoire of extremely good work. I think there is a great deal of curiosity about Russian culture in general at the moment, and I think that in some ways it is compensating for the lack of political affinity. It quite often happens like this, when there is a deficit of a rich discourse, either politically or culturally, even within a country, then the arts step in and have that conversation.

Garsington Opera Pavilion and lake / Credit: Clive Barda

AP: This leads to my next question about your time in Moscow in 1979. Could you tell us more about this experience of working in Russia at that time?

MB: Yes, it was an extraordinary experience. I had heard that towards the end of Brezhnev’s time there was just a certain amount of permission being given to the theatre or the theatre was managing to subvert censorship in an interesting way, reviving some of the great traditions of the early twentieth century, of the post-revolutionary period. Theatre directors were being seen as a very important voice. I was lucky enough to meet and interview Anatoly Efros when he came to the Edinburgh festival with his A Month in a Countryside and Marriage productions. At that time I had been given the British Council fellowship, but the Soviet Ministry of Culture had not responded. The Malaya Bronnya Theatre in Moscow organised for me to come over to do an internship with them, and it was just in the end of Efros’ time at Malaya Bronnaya.

Anatoly Efros / Courtesy of www.efros.com

It was an invaluable experience of being in a culture where at that time theatre was probably the most important art form, because it combined the ability to be articulate about the culture with the quality of being very difficult to censor. Books could be refused publication, while a live theatre performance was a more slippery beast, that could pass the KGB man in a rehearsal room. He could not stop the inventiveness of the rehearsal. Therefore, the potential of the theatre to be such an important art form and its responsibility: that was something I brought back with me. The other thing was just a sense of the great Russian tradition of directors, springing from, on one hand, Stanislavsky, on another hand – Meyerhold.

AP: You are working with opera now, do you have any favourite composers?

MB: I am still a baby in opera terms, but my favourite composer is Claudio Monteverdi. I was not sure if I would enjoy the nineteenth century ‘proper’ opera, but I have enjoyed working on Tchaikovsky’s work enormously. It is much more robust and much less sentimental than I had feared.

AP: We know that there are aspiring directors in our readership, who would be interested to hear some your thoughts on how to break into the profession. Do you have any career advice you can share with them?

MB: Theatre is a collaborative art form, so the most important thing is to find good allies, whose work you admire, whether they are actors, singers, conductors, designers or movement specialists. Try and find people whose work inspired you, and work with them and learn from them.

AP: What are your future plans? Are you thinking about working with opera again?

MB: Yes, I am committed to work on Pelléas et Mélisande by Claude Debussy at Garsington next year. This year I am also working on a musical with the National Theatre, and, at Hampstead, The Intelligent Homosexual’s Guide to Capitalism and Socialism With a Key to the Scriptures, by Tony Kushner. In the meantime I am working on a production of The Cherry Orchard, which I am doing a version of, a new translation.

AP: Michael, thank you and good luck with your future projects!

Eugene Onegin by Pyotr Tchaikovsky At Garsington Opera, Wormsley 3, 5, 11, 16, 18, 25, 29 June 1, 5, 7 July 2016

There are also free public screenings of a live performances of Eugene Onegin from Garsington Opera in the following areas:

SKEGNESS Saturday 2 July 12.30pm

RAMSGATE Saturday 23 July

BRIDGEWATER & BURNHAM Saturday 20 August

GRIMSBY Friday 30 September

Please visit the Garsington Opera website to learn more.

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.