INTERVIEW: James Hill on his ‘Russian Veterans’ project at Pushkin House

Anna Prosvetova met with James Hill, a Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer, before the opening of Russian Veterans exhibition at Pushkin House. James has lived and worked in Russia since the 1990s, and during four consecutive years he went to Gorky Park on Victory Day to photograph over 500 veterans. We talked with James about some of these portraits, exhibited at Pushkin House, influences and inspirations behind this work and the artist’s future projects.

Anna Prosvetova: James, thank you for taking time to meet with us before the opening of your exhibition at Pushkin House. Could you tell our readers about your project, part of which is displayed at the Russian Veterans exhibition?

James Hill: I think anyone at any job always has many ideas they would like to follow through. I have been working in the former Soviet Union since 1991 and I have seen a lot of veterans, great colourful people. In the early 1990s they were much younger, and then by the time we came to the mid 2000s I suddenly realised that these people are not going to be around for much longer. I decided to go to Gorky Park and take their pictures. From the beginning I decided to take photographs of women. It is such an enormous subject, so I thought where to start and decided to do something quite concentrated, focused. I have decided to look at women because it was the greatest mobilization of women in history; there were five hundred thousands women sent to the Front. Also I felt that this was an area which was not particularly well documented, because my impression was that most of the Soviet and Russian work on veterans was very much centered on officers.

In 2006 I went down to the park for the first time and it was a great experience. It was really interesting to meet these people. I have been a war photographer for a long time and my father had been in the military as well as a great part of my family, so I have always been interested in this subject. It interests me what happens afterwards to these people. What I find curious about these veterans is that they went through one of the most brutal conflicts by any standards. Everyone knows that what we call in Britain ‘the Eastern Front’ was the most ferocious on the European territory from the physical conditions point of view, the weather and the brutality of the whole situation there. Therefore, it was very interesting for me to meet with these people. I was curious to see what these people would be like.

Ivanova, b. 1924, Signaller, Anti-Aircraft Defence, and Semyonov, b. 1921, Marine, Northern, Pacific and Black Sea Fleets, Moscow 2006 / Courtesy of Pushkin House

AP: You are a war photographer. How has this experience informed your Veterans project?

JH: I think there is a common language in photography, because there are two very separate roles: being the observer and being the participant. One of the issues of that I have had with being a photographer is precisely the nature of this role, because it is a rather fake concept: I am here, but I am not really here. You are watching people dying in front of you, and you act as you are not really a part of this, but of course you are. What interests me in the relations between being observer and witness. You see scenes which were truly horrifying and which I had to live with afterwards. But when you have to watch your comrade dying next to you, it is surely a very disturbing experience, and I was curious about that. I wanted to see how these people were after this. These people, of course, are heroes; that to me was not an issue. I was interested to see how they have lived with this for sixty years, with these images and ideas. In a sense you may say it is also a psychological study of these people, because I am not the first person to photograph Russian veterans and I would not be the last one, but what interested me was more who they were, what kind of people.

AP: Why did you decide to stage each photograph as a portrait on a plain background? Doesn’t that remove any context from the sitter?

JH: Yes, I have chosen this deliberate format because it is a much more concentrated form. In other words, in 35-millimetre film you have a wider image. Here you cut off the sides; it is much more focused. I have also decided to photograph them on the white background, because I think the plainer the background, the more colourful the person. I knew that I wanted to hear them speaking, and these images are the silent words, but I wanted to hear these words as coming from this person.

AP: Is it also the reason why you have to photograph in chosen black and white?

JH: I do not have any certain preference in this sense. With each project that I do I feel that one approach might work better than the other. In this case I held that it would be more uniformed to do it in black and white. I wanted something that would not be distracting by the format and by the colour. In these photographs I really wanted to focus on an individual.

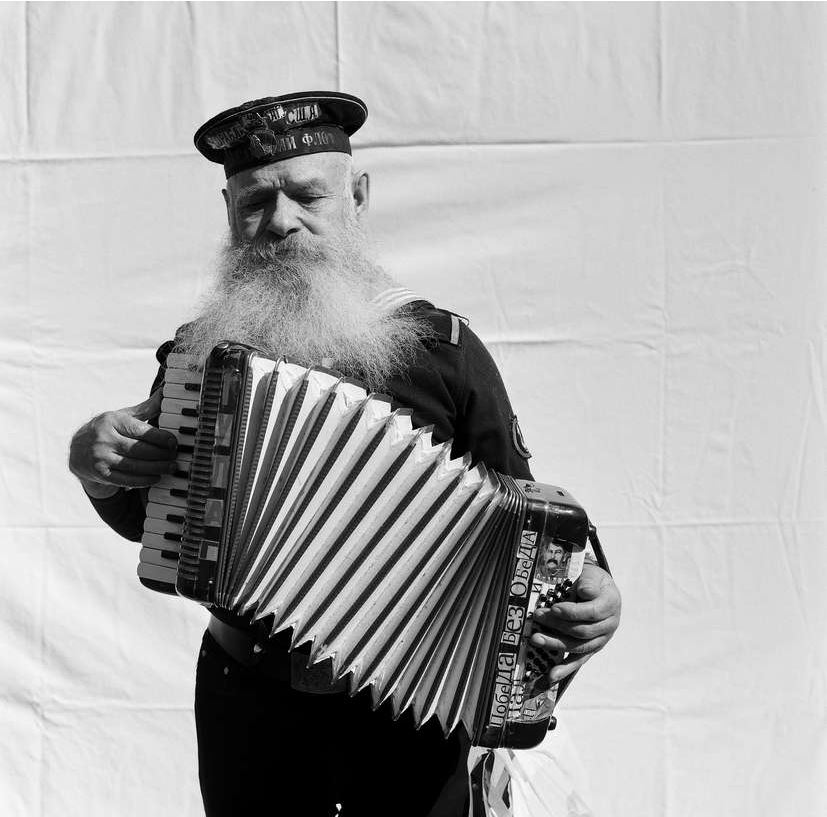

Sailors of the Baltic, Northern and Pacific Fleets, Moscow, 2008 / Courtesy of Pushkin House

AP: The images from this project were recently published as a book, Victory Day. *Have you ever thought about complementing these images with texts in the book?

JH: The difficulty of the veteran story is that it is enormous. How would you tell the story of the World War II? It is deeply rooted also in today even after seventy years. I also wanted something that was very simple. There is an introduction in the book by a writer Boris Vasiliev. I went to him and showed him my photographs. He asked me what I would like to have and I replied that I want to know what it was like from an ordinary soldier in the war. I did not want to know how the Generals saw it, or Stalin or how Soviet historians saw it. I wanted to know how he saw it, how these people saw it. He agreed to write the introduction, and the text has a very moving story about the day he found out that the war had started, when all these seventeen-years old boys were shouting “Hurrah!”; they wanted to go fighting and knew very little about the actual war. What comes out in the end of it is what was interesting to me. I just felt that adding text might be something that could complicate rather than clarify. You know who they are, when they were born, where they served, and let the rest of the story to be formed based only on this information. I thought that words would complicate rather than clarify. I felt that the simplicity of it is what makes it strong.

AP: You have worked on this project for four years. When did you feel that you have reached the end? How did you decide when was the moment to stop?

JH: One of the reasons I have decided to close the project is that I have got a chance to do the book as the British Government wanted to pay for the publication. It coincided with the 65th anniversary and it seemed a logical moment to put it together as a book. I have taken around 500 pictures, and each time it was a lot of effort, it was a very tiring process every year: I would be there from 9 am till 7 pm. It was also emotionally exhausting and moving to do the project.

AP: You have lived both in Ukraine and Russia since 1991. Why did you decide to move there?

JH: I lived in Ukraine from 1991 to 1995, then in Russia from 1995 to 1998. Then I lived in Rome until 2003, and since then I have been living in Moscow. I really wanted to go to Russia from the beginning, but I could not get a visa to go there, so I went to Ukraine. I have studied history in the University of Oxford and then I went to do a course in photojournalism at London College of Communication. It was the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall and Eastern Europe was really a place of focus, where everything was happening and everybody was waiting for the fall of the Soviet Union.

Alexander Rodchenko, Pozharnaia lestnitsa, from the series Dom na Miasnitskoi (Fire Escape, from the series Building on Miasnitskaia Street), 1925 / Courtesy of San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

AP: In one of your interviews you mentioned that you are inspired by August Sander and Irving Penn in your work. Could you name any Russian photographers whose work you find especially interesting?

JH: Yes, these are my two favourites, and this project is a dedication of some sort to their work. I have not done as many portrait series as I would like to because I have spent a lot of time doing photojournalistic work. What I find really interesting about their work is that there is something very eternal about these portraits. The style of dresses might change, the place might change, but there is so much to be felt in the images of people they have created. It is a little bit of a homage to these masters, because I just felt that you can read all the books that you want, but when you look at those photographs by Sander with the boxer, the cook, the bricklayer or the students walking down the street in their Sunday best outfit on the way to church. You have such a feeling for the time these people were living in and the stories behind their images being told.

After sixty five years you could know all about World War II by looking at these people in my photographs, and I feel that portraits when they are good there is something eternal about them. I can really look at these portraits again and again. Remember out of 500 images in total there are only 70 photographs in the book, I had to cut down those that were less interesting. There were no rules to decide which is better; it is just my personal feeling.

As for the Russian photography, I think Alexander Rodchenko is one of the greats, not only in Russia, but in photography in general. He was somebody who really saw it. You have a certain conversation with these photographers, because you think: “What if he would tilt the camera a little bit like this or shoot at this angle?” That whole avant-garde era is very powerful photography and I think still stands out today as being a really great work, but Rodchenko was someone beyond that. He was some kind of non-formalist formalist. When you look at his pictures, you feel like he is rewriting the whole book every time. His work is extraordinary exciting and beautiful, with diagonals and shapes. You have to pay homage to those who see it better then you do.

AP: Could you tell us about your future projects?

JH: I have just finished my recent book, Somewhere between War and Peace, and I am working on two projects in Moscow at the moment. The main one is about impressions from the city and it is called Black Square / Red Square. It is sort of homage to Moscow as an inspiration. There have been a lot of work done on St Petersburg, and Moscow space is somehow neglected. It still needs to be shaped, but basically it is a collection of all the work I have done in Moscow. It is the city’s architecture, people, basically everything. There is already a big body of work, but I am adding to it, I am not really happy with what I have at the moment and hopefully will finish it by the end of this year.

AP: Do you have any further plans for the Veterans project?

JH: I am very happy to say that Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow now has ten photographs from this series in their collection as well as The Lumiere brothers Center for Photography in Moscow. There is also an exhibition opening in Kazan with eighteen of these pictures. Soon there will none of these guys left and that is one of the reasons why I was glad to give this exhibit to Russian institutions. These images are important today, but their importance will increase in twenty years time.

AP: James, thank you very much!

At Pushkin House

7 May – 9 June

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.

Fyodor Grigoryevich Bortsov, b. 1927, Driver, Diver, Machine-Gunner, Electrician, Motor Torpedo Boats, Pacific Fleet, Moscow, 2008 / Courtesy of Pushkin House