INTERVIEW: Julia Tulovsky from Zimmerli Art Museum talks about Oleg Vassiliev and Non-Conformist Soviet Art

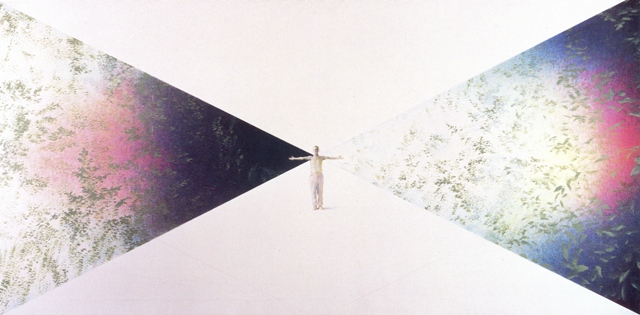

Above: Oleg Vassiliev, DEEP SPACE, 1986 / Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery

The Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum is part of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. The Zimmerli’s Russian and Soviet Non-Conformist art collection contains over 22,000 objects spanning the fourteenth century to the present. We talked with Julia Tulovsky, Associate Curator of Russian and Soviet Nonconformist Art, about Oleg Vassiliev: Space and Light exhibition, featuring paintings and works on paper by Russian artist Oleg Vassiliev (1931-2013), a defining figure in Russian contemporary art.

Oleg Vassiliev, HOUSE ON ISLAND ANZER, 1965 / Courtesy of Saatchi Gallery

Anna Prosvetova: I would like to start our conversation with a question about the exhibition of Oleg Vassiliev at Zimmerli museum. How did the idea of this show come about?

Julia Tulovsky: I have been thinking about the exhibition of works by Oleg Vassiliev for a long time already, because I believe that he is one of the major Russian painters; he is a very subtle one. As you might know, he was a very close friend with Ilya Kabakov and Eric Bulatov. Of course, he knew many artists of the period, but these two painters have been his childhood friends. They spent a lot of time together, discussing art and their works. Nowadays Kabakov and Bulatov are one of the most famous artists, representatives of Soviet nonconformist environment, and Vassiliev could be placed on the same level with these artists. However, I think that due to some circumstances of his life his art was not appreciated, as it should have been. Therefore, once I have received an opportunity to organise his exhibition, I was very happy to fulfill this project. His art is an amazing material; I have not seen many examples of paintings and drawings executed in such a gentle and subtle manner.

AP: I agree. Reading materials on the exhibition and looking at the paintings, it is quite evident that Vassiliev’s works are very different from works by Kabakov and Bulatov, for example. I could even say that they are very poetic.

JT: Yes, he was not interested in political issues, on contrary to Kabakov and Bulatov. Vassiliev was more intrigued by the exploration of the visual form, the space inside a painting, constructed with light. That is why the exhibition was called The Space and The Light. At the same time, if we look at the composition in his works and their visual features, certain similarities with art of Kabakov and Bulatov become evident. Especially with Bulatov, with whom Vassiliev worked very closely, almost sharing the same studio for many years. One may also find parallels and connections with works by other artists here. I met Oleg several times at art openings, but did not have a chance to know him personally. According to memories of people who knew him, his contemporaries and friends, and also to his own writings, the continuity of perception and the artistic world he was creating and sharing with the viewer were the most significant features of his art.

AP: You have mentioned the artist’s writings. Did he somehow put into words his artistic approach? Are there any manifestoes or publications of the artist’s writings directly talking about his art and vision?

JT: Yes, there is a book called The Windows of Memory, published by NLO. This book consists of both Vassiliev’s memories and memories of his contemporaries. Here the artist described some works he thought were key for his career. In particular, he mentionedA House of the Island Anzer, 1965, which he perceived as the beginning of his independent career, The Diagonal, a self-portrait with a cross, An Autumn Portrait, where he depicted his wife Kira, and some others.

AP: Are there any publications accompany the exhibition?

JT: Yes, there is a catalogue with several articles by different academics reflecting on Vassiliev’s work. In my introduction to the catalogue I have described ideas and approaches I have had while organising the show, my intention to showcase the development of Vassiliev’s style and his approach to construction of the picture space with the light. First, he was interested in the creation of the space contained inside the picture plane, then he opened up this space to the viewer, and later he combined these two approaches. The catalogue also includes articles by Andrew Solomon and Robert Storr on perception of Russian art in the West.

AP: In our recent interview with Oleg Tselkov, a Vassiliev’s contemporary, he mentioned that Nonconformism did not exist as an artistic group, but more as a social movement, attracting variety of artists and creative approaches outside the official art. Do you agree with this statement and how could you define Nonconformism?

JT: I absolutely agree with this statement. It is better to define Non-Conformism not as an artistic movement, but as an epoch that united artists who did not follow the requirements of the official Soviet art. Of course, it included artists with absolutely different visions and techniques, numerous movements and groups, but also artists who worked in between these main streams, combining features of official and underground art in their works, going beyond the frames of accepted art. So, it is difficult to gather these artists in a movement; Nonconformism is a historical period.

AP: Could you trace any Western influences in Vassiliev’s work?

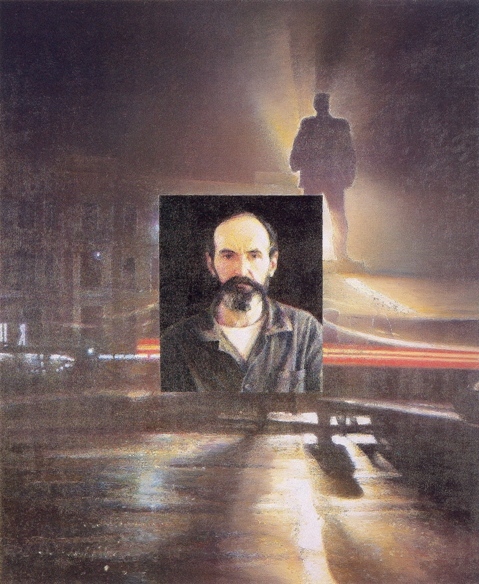

Oleg Vassiliev, DIAGONAL, 1977 / Courtesy of olegvassiliev.com

JT: It is not easy to answer this question. In other artists’ works one could trace some evident parallels or influences of different artists or artistic movements, but it is not the case with Vassiliev. I was thinking about it during the preparation of the exhibition, and could not identify any direct influences in his work. Therefore, one could say that his art is unique. There are many artists who examined the light and its features, but their work is still slightly different from Vassiliev’s. For instance, Robert Storr compares him to Richter, but I think Vassiliev work is absolutely different in its nature, foundation. There were various indirect influences, the circle of similar ideas that have been developing at the same time by different artists, but it led to different outcomes.

At the same time, his art is quite universal from the perception point of view. The artists who directly referenced the Soviet reality in their work were closely connected with it, and in order to understand their art one should have some knowledge about this Soviet context. Vassiliev, on contrary, combining features of the nineteenth-century art, the Wanderers, and also of Russian Avant-garde, could be easily perceived as a universal contemporary artist, because he deals with themes of memory, consciousness and pure pictorial aspects that viewers could understand without knowing about this specific cultural background.

AP: Did you have any interesting feedback from visitors, taking into account that the exhibition took place outside Russia?

JT: Our museum is located a little bit outside of the main cultural centre, outside of New York. Therefore, our audience is very diverse, including people who work in arts and come from New York to see the show, Americans and Russians, students from the Rutgers University or local people who visit the museum on Sundays. And we have seen that wider public is very much attracted to Vassiliev’s work. For instance, during the opening of the exhibition and the presentation of its catalogue, I have had to conduct an additional tour of the show. There was a number of people who came late due to the weather conditions, and they have asked me to repeat the tour for them. During this tour I have noticed that people from the first group also joined us for the second time, because they were very interested in and inspired by the works. Some people were also asking me if it is possible to buy his works and what is the price.

AP: This is another aspect I wanted to talk about. The major part of the museum’s collection is a private gift from Norton and Nancy Dodge. There were among other Western private collectors interested in nonconformist Soviet art. Why do you think works of this period were and remain popular among Western collectors?

Oleg Vassiliev/ MAYAKOVSKY SQUARE, ERIC BULATOV, 1995 / Courtesy of olegvassiliev.com

JT: I do not really think that Soviet artists, such as Eric Bulatov or Dmitry Prigov, are better known in the West than in Russia. These artists are familiar to art historians, both in Russia and in western countries, who work with this period. They are not widely known to the general audience though. I do not think that Oleg is better known in the West than in Russia. His work is familiar to a very narrow circle of people, who study and appreciate his art. Here we even have a small group of people who knew him personally and who like his work. And I think even specialists, who knew his name, were not aware of the scale of his work and talent. There was a small number of his exhibitions and his works were generally underrepresented. Even people, who work in arts, in galleries or museums, or artists came to me afterwards, saying that they were very impressed by the show and it made them look at Oleg’s work in a different light.

AP: And where did the majority of the works for this exhibition come from? From the museum’s collection?

JT: This exhibition presents 83 works from American collections only. Almost half of it, around 38 works, came from our collection, and the rest came from private collections in the US. Oleg lived in New York and, therefore, American collectors have been buying his works. His works are also included in some European collections. Of course, there is a number of good works by Oleg Vassiliev in Europe, but due to some logistic difficulties we have decided to restrict our choice to America only. We would be happy to supplement this show with other works from European collections and present it somewhere in Europe, in London, but not at this moment. I believe there is an interest in this show, and we would be glad to cooperate with another institution in order to bring it to Europe and may be to Russia also.

AP: Do you think there are more artists in these private collections you have worked with to discover in future?

JT: I think there are more to discover in European collections.

AP: There is a current exhibition in the museum called The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection of Nonconformist Art from the Soviet Union, on view until 31 August. Does it showcase the collection’s highlights or its display is constantly changing in order to present greater number of works from the collection? Do you plan to produce an updated version of the collection’s catalogue?

JT: It is a permanent display, though we change some sections from time to time. As for new publications, we are currently working on our translation of artists’ writings and planning to prepare a new edition of the collection’s catalogue, but it is still work in progress.

AP: Do you add new works in your Soviet art collection or is it a closed one?

JT: Yes, we are enlarging our collection – sometimes with works we acquire, sometimes with works we receive as private gifts. The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection is limited by the Soviet period, because for the collector it was a crucial aspect: he collected forbidden art, art under censorship. However, we also have another collection comprised of a more contemporary art from 1990s and 2000s, and I would like to continue expansion of this collection. It is interesting to follow the current situation in Russian art. Developing this part of the collection, we could add a new, topical meaning to The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection, turning it into an open material, not a closed, separated part reflecting only a certain period.

We have recently received a new gift from Claude and Nina Gruen from California, which brings in contemporary works by Russian artists and allows us to develop further the existing collection. For example, this collection includes works by such artists as Konstantin Zvezdochetov, Sergei Shutov and others. We have organised an exhibition of this gift in 2009 and published the catalogue.

AP: And what do you think about the current situation with contemporary art in Russia? Do you have any certain names you would like to highlight?

JT: I do not feel that I have enough information to talk about this topic right now. I just think that contemporary art in Russia is not appreciated and studied as much as it should be. Nonconformist artists are not very well studied either, but at least we know their names and there are people who work with their art. As for next generation of contemporary artists, after the Soviet Union, it remains unknown for major part: nobody explores their works and their names are falling out from art historical studies. I hope this situation will change in future.

AP: Do you think contemporary art in Russia today has any social significance, as it was in the Soviet era?

JT: I think there is no great interest in contemporary art among wider audience in Russia today. Nonconformists were producing forbidden art, and their works were seen as a gasp of fresh air, of freedom for intelligentsia. Today art is not something forbidden in Russia, and the state does not impose any boundaries on the artists’ activity. At the same time, there are almost no structures for artist’ support or developed art market. There are state institutions and museums that do some beneficial work in this field, but there is no infrastructure in general similar to western countries.

Some time ago I was working on an exhibition of photographic portraits of Non-conformist artists in order to show the audience how they looked like. There were many pictures by Igor Palmin, a Soviet photographer, who was taking big portraits of these artists in 1970s, because it was important to save images of these people. And after visiting this show one of contemporary artists said that it would be impossible to prepare a similar exhibition on their generation, because there is simply no material. Now there is no such unifying factor as an opposition to the state, as it was in the Soviet Union.

AP: There are some works from the museum’s collection displayed at the current exhibition at Saatchi Gallery in London. What do you think about this show?

JT: I think it is a very interesting exhibition, especially its idea to combine Russian, Western and Chinese artists in one space. Usually, Russian art is displayed separately, without its placement into the context of Western art. An exhibition should include both Russian and Western works in order to give the audience an opportunity to compare and contrast. I think that Russian artists in the framework of this exhibition look really great and this strategy should be developed in future projects in order to introduce names of Russian artists into a wider art historical context.

AP: And my last question is about the museum’s future projects. Could you tell us a little bit more about it?

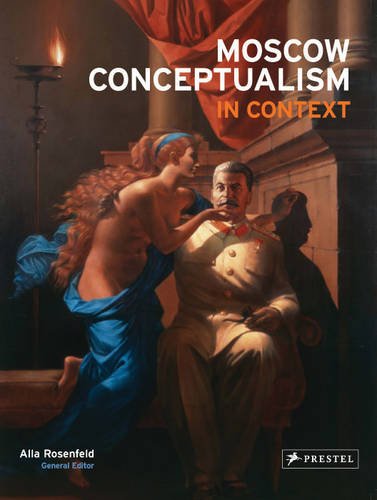

JT: We are preparing an exhibition on Moscow Conceptualism. Initially it has been planned to open together with the publication of the book, Moscow Conceptualism in Context, 2011, but was postponed due to various technical reasons. We are planning to open it in 2016.

At the same time we are planning a series of exhibitions showcasing works by Nonconformist artists in order to introduce them to the audience. The Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection has almost an encyclopaedic character and contains a number of great artists who are not very well-known today. I believe this collection does not have any analogues from the coverage point of view. It consists of more than 20 000 works, excluding the archive documents, with works from Moscow, Saint Petersburg and the majority of Soviet Republics. It has many early works, because Norton Dodge started collecting in 1960-70s, when these artists just began their activity. I do not think there is another similar collection like this in Europe or America.

AP: Julia, thank you! Looking forward to your new show!

This interview was originally published on Russian Art and Culture.